- Home

- Mildred A. Wirt

The Girl Detective Megapack: 25 Classic Mystery Novels for Girls Page 9

The Girl Detective Megapack: 25 Classic Mystery Novels for Girls Read online

Page 9

“Do you like her?” inquired Mrs. Gay.

“No, I don’t. But in a way I feel sorry for her.”

Mary Louise followed her mother into the dining room and for the next fifteen minutes gave herself up to the enjoyment of the lovely lunch of dainty sandwiches and refreshing iced tea which her mother had so carefully prepared. It was not until she had finished that she began her story of the robbery at Dark Cedars and of her own and Jane’s part in the partial recovery of the money. She made no mention, however, of the bandit who had tried to hold them up, or of the queer disturbances at night at Dark Cedars. She concluded with the old lady’s request that they—Mary Louise and Jane—stay with Elsie and watch her.

Mrs. Gay looked a little doubtful.

“I don’t know, dear,” she said. “Something might happen. Still, if Mrs. Patterson is willing to let Jane go, I suppose I will say yes.”

Fifteen minutes later Mary Louise whistled for her chum and put the proposition up to her.

Jane shivered.

“I’m not going to stay in that spooky old place!” she protested. “Not after what happened there last night.”

“‘Who’s afraid of the big, bad wolf?’” teased Mary Louise. “Jane, I thought you had more sense!”

“There’s something uncanny about Dark Cedars, Mary Lou, and you know it! Not just that the house is old, and the boards creak, and there aren’t any electric lights. There’s something evil there.”

“Of course there is. But that’s the very reason it thrills me. I don’t agree with Miss Grant and just want to go there because I believe Elsie is guilty of stealing that gold and that maybe we can find out where she has hidden it. Somebody else took it, I’m sure—and that somebody keeps coming back to Dark Cedars to get something else. Something valuable, ‘precious to me,’ Miss Grant called it. And we’ve got to catch them!”

“You didn’t tell your mother that?”

“No. I told her about only what has actually been stolen so far. No need to alarm her. And will you do the same with your mother?”

Jane rose reluctantly.

“I suppose so. If you’ve made up your mind to go through with it, you’ll do it. I know you well enough for that. And I don’t want you over there at Dark Cedars alone—or only with Elsie. Even Hannah and William are moving out, you remember.… Yes, I’ll go. If Mother will let me.”

“You’re a peach, Jane!” cried her chum joyfully.

It was several hours, however, before the girls actually started to Dark Cedars. Arrangements for the picnic the following day had to be completed; their suitcases had to be packed, and their boy-friends called on the telephone. It was after five o’clock when they were finally ready.

From the porch of Mary Louise’s house they saw Max Miller drive up in his car.

“I’m taking you over,” he announced, for Mary Louise had told him that she and Jane were visiting Elsie Grant for a few days.

“That’s nice, Max,” replied Mary Louise. “We weren’t so keen about carrying these suitcases in all this heat.”

“It is terribly hot, isn’t it?” remarked Mrs. Gay. “I’m afraid there will be a thunderstorm before the day is over.”

Jane made a face. Dark Cedars was gloomy enough without a storm to make it seem worse.

“Come on, Silky!” called Mary Louise. “We’re taking you this time.”

“I’ll say we are!” exclaimed her chum emphatically.

Elsie Grant was delighted to see them. She came running from behind the hedge attired in her pink linen dress and her white shoes. Mary Louise was thankful that Max did not see her in the old purple calico. His sense of humor might have got the better of him and brought forth a wisecrack or two.

As soon as they were out of the car she introduced them to each other.

“You didn’t know we were coming for a visit, did you, Elsie?” she inquired. “Well, I’ll tell you how it happened: Your aunt Mattie is in the hospital for an operation, and she wanted Jane and me to stay with you while she was away.”

The girl wrinkled her brows.

“It doesn’t sound like Aunt Mattie,” she said, “to be so thoughtful of me. She must have some other motive besides pity for my loneliness.”

“She has!” cried Jane. “You can be sure—”

Mary Louise put her finger to her lips.

“We’ll tell you all about it later,” she whispered while Max was getting the suitcases from the rumble seat. “It’s quite a story.”

“Is Hannah still here?” inquired Jane. “Or do we cook our own supper?”

“Yes, she’s here,” answered Elsie. “She expects to come every day to work in the house, and William will take care of the garden and the chickens and milk the cow just the same. But they’re going away every night after supper.”

Max, overhearing the last remark, looked disapproving.

“You don’t mean to tell me you three girls will be here alone every night?” he demanded. “You’re at least half a mile from the nearest house.”

“Oh, don’t worry, Max, we’ll be all right,” returned Mary Louise lightly. “There’s a family of colored people who live in a shack down in the valley behind the house. We can call on them if it is necessary.”

“Speaking of them,” remarked Elsie, “reminds me that William says half a dozen chickens must have been stolen last night. At least, they’re missing, and of course he blames Abraham Lincoln Jones. But I don’t believe it. Mr. Jones is a deacon in the Riverside Colored Church, and his wife is the kindest woman. I often stop in to see her, and she gives me gingerbread.”

Mary Louise and Jane exchanged significant looks. Perhaps this colored family was the explanation of the mysterious disturbances about Dark Cedars.

Mary Louise suggested this to Elsie after Max had driven away with a promise to call for the girls at nine o’clock the following morning.

“I don’t think so,” said Elsie. “But of course it’s possible.”

“Let’s walk over to see this family after supper,” put in Jane. “We might learn a lot.”

“All right,” agreed Elsie, “if a storm doesn’t come up to stop us.… Now, come on upstairs and unpack. What room are you going to sleep in—Hannah’s or Aunt Mattie’s—or up in the attic with me?”

“We have to sleep in your aunt Mattie’s bedroom,” replied Mary Louise. “I promised we would.”

Elsie looked disappointed.

“You’ll be so far away from me!” she exclaimed.

“Why don’t you sleep on the second floor too?” inquired Jane.

“There isn’t any room that’s furnished as a bedroom, except Hannah’s, and I think she still has her things in that. Besides, Aunt Mattie wouldn’t like it.”

“Oh, well, we’ll leave our door open,” promised Jane.

“No, we can’t do that either,” asserted Mary Louise. “Miss Grant told me to close it.”

“Good gracious!” exclaimed her chum. “What next?”

“Supper’s ready!” called Hannah from the kitchen.

“So that’s next,” laughed Mary Louise. “Well, we’ll unpack after supper. I’m not very hungry—I had lunch so late—but I guess I can eat.”

Hannah came into the dining room and sat down in a chair beside the window while the girls ate their supper, so that she might hear the news of her mistress. Mary Louise told everything—the capture of the bills, the part Harry Grant played in the affair, and Corinne Pearson’s guilt in the actual stealing. She went on to describe Miss Grant’s collapse and removal to the Riverside Hospital, concluding with her request that the two girls stay with Elsie while she was away.

“So she still thinks I stole her gold pieces!” cried the orphan miserably.

“I’m afraid she does, Elsie,” admitted Mary Louise. “But there’s something else she’s worrying about. What could Miss Grant possibly own, Hannah, that she’s afraid of losing?”

“I don’t know for sure,” replied the servant. “But I’ll

tell you what I think—if you won’t laugh at me.”

“Of course we won’t, Hannah,” promised Jane.

“Well, there was something years ago that old Mr. Grant got hold of—something valuable—that I made out didn’t belong to him. I don’t know what it was—never did know—but I’d hear Mrs. Grant—that was Miss Mattie’s mother, you understand—tryin’ to get him to give it back. ‘It can’t do us no good,’ she’d say—or words like them. And he’d always tell her that he meant to keep it for a while; if they lost everything else, this possession would keep ’em out of the poorhouse for a spell. Mrs. Grant kept askin’ him whereabouts it was hidden, and he just laughed at her. I believe she died without ever findin’ out.…

“Well, whatever it was, Mr. Grant must have give it to Miss Mattie when he died, and she kept it hid somewheres in this house. No ordinary place, or I’d have found it in house-cleanin’. You can’t houseclean for forty years, twicet a year, without knowin’ ’bout everything in a house.… But I never seen nuthin’ valuable outside that safe of her’n.

“So what I think is,” continued Hannah, keeping her eyes fixed on Mary Louise, “that Mrs. Grant can’t rest in her grave till that thing is give back to whoever it belongs to. I believe her spirit visits this house at night, lookin’ for it, and turnin’ things upside down to find it. That’s why nuthin’ ain’t never stolen. So anybody that lives here ain’t goin’ have no peace at nights till she finds it.”

Hannah stopped talking, and, as Jane had promised, nobody laughed. As a matter of fact, nobody felt like laughing. The woman’s belief in her explanation was too sincere to be derided. The girls sat perfectly still, forgetting even to eat, thinking solemnly of what she had told them.

“We’ll have to find out what the thing is,” announced Mary Louise finally, “if we expect to make any headway. I wish I could go see Miss Mattie at the hospital tomorrow.”

“Well, you can’t,” said Jane firmly. “You’re going to that picnic. We can ask the gypsies when we have our fortunes told.”

“Gypsies!” exclaimed Hannah scornfully. “Gypsies ain’t no good! They used to camp around here till they drove Miss Mattie wild and she got the police after ’em. Don’t have nuthin’ to do with gypsies!”

“We’re just going to have our fortunes told,” explained Jane. “We don’t expect to invite them to our houses.”

“Well, don’t!” was the servant’s warning as she left the room.

When the girls had finished their supper they went upstairs to Miss Grant’s bedroom and unpacked their suitcases. But they were too tired to walk down the hill to call upon Abraham Lincoln Jones. If he wanted to steal chickens tonight, he was welcome to, as far as they were concerned.

Hannah and William left about eight o’clock, locking the kitchen door behind them, and the girls stayed out on the front porch until ten, talking and singing to Jane’s ukulele. The threatening storm had not arrived when they finally went to bed.

It was so still, so hot outdoors that not even a branch moved in the darkness. The very silence was oppressive; Jane was sure that she wouldn’t be able to go to sleep when she got into Miss Mattie’s wooden bed with its ugly carving on the headboard. But, in spite of the heat, both girls dropped off in less than five minutes.

They were awakened sometime after two by a loud clap of thunder. Branches of the trees close to the house were lashing against the windows, and the rain was pouring in. Mary Louise jumped up to shut the window. As she crawled back into bed she heard footsteps in the hall. Light footsteps, scarcely perceptible above the rain. But someone—something—was stealthily approaching their door!

Her instinct was to reach for the electric-light button when she remembered that Miss Grant used only oil lamps. Trembling, she groped in the darkness for her flashlight, on the chair beside her. But before she found it the handle rattled on the door, and it opened—slowly and quietly.

There, dimly perceptible in the blackness of the hall, stood a figure—all in white!

CHAPTER XI

The Picnic

The figure in white remained motionless in the doorway of Miss Grant’s room. Mary Louise continued to sit rigid in the bed, while Jane, who was still lying down, clutched her chum’s arm with a grip that actually hurt.

For a full minute there was no sound in the room. Then a flash of lightning revealed the cause of the girls’ terror.

Mary Louise burst out laughing.

“Elsie!” she cried. “You certainly had us scared!”

Jane sat up angrily.

“What’s the idea, sneaking in like a ghost?” she demanded.

The orphan started to sob.

“I was afraid of waking you,” she explained. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

“Well, it’s all right now,” said Mary Louise soothingly. “Ordinarily we shouldn’t have been scared. But in this house, where everybody talks about seeing ghosts all the time, it’s natural for us to be keyed up.”

“Why that woman doesn’t put in electricity,” muttered Jane, “is more than I can see. It’s positively barbarous!”

“Come over and sit here on the bed, Elsie, and tell us why you came downstairs,” invited Mary Louise. “Are you afraid of the storm?”

“Yes, a little bit. But I thought I heard something down in the yard.”

“Old Mrs. Grant’s ghost?” inquired Jane lightly.

“Maybe it was Abraham Lincoln Jones, returning for more chickens,” surmised Mary Louise. “But no, it couldn’t be, or Silky would be barking—he could hear that from the cellar—so it must be just the wind, Elsie. It does make an uncanny sound through all those trees.”

“May I stay here till the storm is over?” asked the girl.

“Certainly.”

If it had not been so hot, Mary Louise would have told Elsie to sleep with them. But three in a bed, and a rather uncomfortable bed at that, was too close quarters on a night like this.

The storm lasted for perhaps an hour, while the girls sat chatting together. As the thundering subsided, Jane began to yawn.

“Suppose I go up to the attic and sleep with Elsie?” she said to Mary Louise, “if you’re not afraid to stay in this room by yourself.”

“Of course I’m not!” replied her chum. “I think that’s a fine idea, and your being there will prevent Elsie from being nervous and hearing things. Does it suit you, Elsie?”

“Yes! Oh, I’d love it! If you’re sure you don’t mind, Mary Louise.”

“I don’t expect to mind anything in about five minutes,” yawned Mary Louise. “I’m dead for sleep.”

She was correct in her surmise: she knew nothing at all until the bright sunshine was pouring into her room and Jane wakened her by throwing a pillow at her head.

“Wake up, lazybones!” she cried. “Don’t you realize that today is the picnic?”

Mary Louise threw the pillow back at her chum and jumped out of bed.

“What a glorious day!” she exclaimed. “And so much cooler.”

Elsie, attired in her new pink linen dress, dashed into the room.

“Oh, this is something like!” she cried. “I haven’t heard any gayety like this for three years!”

“Mary Louise is always ‘Gay,’” remarked Jane demurely. “In fact, she’ll be ‘Gay’ till she gets married.”

Her chum hurled the other pillow from Miss Grant’s bed just as Hannah poked her nose into the room.

“Don’t you girls throw them pillows around!” she commanded. “Miss Mattie is that careful about her bed—she even makes it herself. And at house-cleanin’ time I ain’t allowed to touch it!”

“It’s a wonder she let you sleep on it, Mary Louise,” observed Elsie.

“Made me sleep on it, you mean.” Then, of Hannah, she inquired, “How soon do we have breakfast?”

“Right away, soon as you’re dressed. Then you girls can help pack up some doughnuts and rolls I made for your picnic.”

“You’re an angel, Hanna

h!” exclaimed Mary Louise. To the girls she said, “Scram, if you want me downstairs in two minutes.”

Soon after breakfast the cars arrived. There were three of them—the two sports roadsters belonging to Max Miller and Norman Wilder, and a sedan driven by one of the girls of their crowd, a small, red-haired girl named Hope Dorsey, who looked like Janet Gaynor.

Max had brought an extra boy for Elsie, a junior at high school, by the name of Kenneth Dormer, and Mary Louise introduced him, putting him with Elsie in Max’s rumble seat. She herself got into the front.

“Got your swimming suit, Mary Lou?” asked Max, as he started his car with its usual sudden leap.

“Of course,” she replied. “As a matter of fact, I brought two of them.”

“I hadn’t noticed you were getting that fat!”

“That’s just about enough out of you! I don’t admire the Mae West figure, you know.”

“Then why two suits?” inquired the young man. “Change of costume?”

“One for Elsie and one for me,” explained Mary Louise. “I don’t believe Elsie can swim, but she’ll soon learn. Will you teach her, Max?”

“I don’t think I’ll get a chance to, from the way I saw Ken making eyes at her. He’ll probably have a monopoly on the teaching.”

Mary Louise smiled: this was just the way she wanted things to be.

The picnic grounds near Cooper’s woods were only a couple of miles from Riverside. A wide stream which flowed through the woods had been dammed up for swimming, and here the boys and men of Riverside had built two rough shacks for dressing houses. The cars were no sooner unloaded than the boys and girls dashed for their respective bath houses.

“Last one in the pool is a monkey!” called Max, as he locked his car.

“I guess I’ll be the monkey,” remarked Elsie. “Because I have a suit I’m not familiar with.”

“I’ll help you,” offered Mary Louise.

They were dressed in no time at all; as usual the girls were ahead of the boys. They were all in the water by the time the boys came out of their shack.

The pool was empty except for a few children, so the young people from Riverside had a chance to play water games and to dive to their hearts’ content. Everybody except Elsie Grant knew how to swim, and Mary Louise and several of the others were capable of executing some remarkable stunt diving.

The Secret Pact

The Secret Pact Swamp Island

Swamp Island Signal in the Dark

Signal in the Dark The Secret of the Sundial

The Secret of the Sundial The Wishing Well

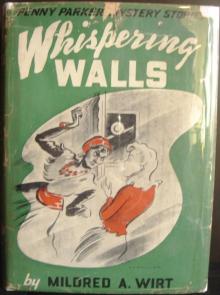

The Wishing Well Whispering Walls

Whispering Walls Hoofbeats on the Turnpike

Hoofbeats on the Turnpike The Deserted Yacht

The Deserted Yacht Dan Carter and the Haunted Castle

Dan Carter and the Haunted Castle Dan Carter and the Great Carved Face

Dan Carter and the Great Carved Face Saboteurs on the River

Saboteurs on the River Dan Carter and the Cub Honor

Dan Carter and the Cub Honor Dan Carter-- Cub Scout

Dan Carter-- Cub Scout Dan Carter, Cub Scout, and the River Camp

Dan Carter, Cub Scout, and the River Camp Dan Carter and the Money Box

Dan Carter and the Money Box The Girl Detective Megapack: 25 Classic Mystery Novels for Girls

The Girl Detective Megapack: 25 Classic Mystery Novels for Girls